| |

By the mid-nineteen-seventies, John Cleese had made his name with the Monty Python team and their series of sketch shows, but would decline to join them in their fourth and final set of programmes, since he wanted to try something else instead. That something was a sitcom that would represent all that was best in the British form of the genre for all time, an acknowledged classic that even now viewers return to: Fawlty Towers. But there was a problem with that for Cleese's career, how do you live up to it afterwards? There were two series, in 1975 and 1979, and he famously never returned to the role of hotelier Basil Fawlty.

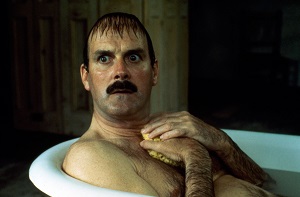

What he did, however, was make Clockwise, a 1986 comedy film written not by him and his then-wife Connie Booth, as Fawlty Towers had been, but by Michael Frayn, a playwright best known in the theatre for Noises Off, the fast-paced farce that should have indicated he and Cleese were a perfect match. The basic premise of the seventies sitcom was that Basil exists in a hostile world where everyone is out to get him, even those who do not realise they are in such a position, and his antagonistic personality not only makes situations worse, but can lead him into personal disaster thanks to his combination of temper and extreme pettiness. What he did, however, was make Clockwise, a 1986 comedy film written not by him and his then-wife Connie Booth, as Fawlty Towers had been, but by Michael Frayn, a playwright best known in the theatre for Noises Off, the fast-paced farce that should have indicated he and Cleese were a perfect match. The basic premise of the seventies sitcom was that Basil exists in a hostile world where everyone is out to get him, even those who do not realise they are in such a position, and his antagonistic personality not only makes situations worse, but can lead him into personal disaster thanks to his combination of temper and extreme pettiness.

Take episode five of series one, The Hotel Inspectors, which had the benefit of one of the finest guest stars they ever enjoyed the presence of, Bernard Cribbins. As written, his Mr Hutchinson is as absurd as Basil is, using over-ornate language and causing problems thanks to his insistence on everything being just so. Watching him and Cleese drive each other up the wall, to the point of violence, is one of the more relishable instances of the comedy of the period, and a perfect example of how Cleese's humour essentially relied on his characters losing control in a crisis they have partly visited upon their own heads. Which brings us to Clockwise.

Frayn wrote the screenplay inspired by his own poor timekeeping and thought it would be amusing to exact revenge on all those who complained of his lateness by visiting a chapter of accidents upon his lead character, a stickler for being punctual. He was Brian Stimpson, played by Cleese, a headmaster at an English comprehensive school who rules his pupils with a rod of iron, figuratively if not literally, keeping tabs on every one of them and all the staff into the bargain. He has his days all planned out to the nanosecond, but as you may anticipate, he will be heading for a fall pretty soon when he is invited to become chairman of a headmasters' conference. Frayn wrote the screenplay inspired by his own poor timekeeping and thought it would be amusing to exact revenge on all those who complained of his lateness by visiting a chapter of accidents upon his lead character, a stickler for being punctual. He was Brian Stimpson, played by Cleese, a headmaster at an English comprehensive school who rules his pupils with a rod of iron, figuratively if not literally, keeping tabs on every one of them and all the staff into the bargain. He has his days all planned out to the nanosecond, but as you may anticipate, he will be heading for a fall pretty soon when he is invited to become chairman of a headmasters' conference.

In fact, his main error is a quirk of speech: he will say the word "right" over and over to confirm or affirm what someone else has said, and that becomes a liability when he gets mixed up over which train to catch - he should have gone for the one on the left, but kept saying "right" to the ticket inspector and was confused. He did not know he was confused until he realised he was on the wrong carriage, which was where the escalating series of personal disasters kicked off, although he does make another error of judgement - when he returns home to catch his wife (Alison Steadman), he seems to forget he has a phone, and could have called another taxi.

Or the hospital where she was working, for that matter. This position of privilege the audience has over Stimpson, where we can see where he is going wrong, is the format of classic farce, and Cleese was quick to praise Frayn's work, Cleese being obsessed with the mechanisms of comedy to the extent that they constructed his next big screen effort, A Fish Called Wanda, to the letter. This exacting approach to humour, either from the writer or star, could go either way, to hilarity for some audiences impressed at the intelligence of its technique, or to a lack of reaction for others for whom the lack of spontaneity in each sequence was a real sticking point. Or the hospital where she was working, for that matter. This position of privilege the audience has over Stimpson, where we can see where he is going wrong, is the format of classic farce, and Cleese was quick to praise Frayn's work, Cleese being obsessed with the mechanisms of comedy to the extent that they constructed his next big screen effort, A Fish Called Wanda, to the letter. This exacting approach to humour, either from the writer or star, could go either way, to hilarity for some audiences impressed at the intelligence of its technique, or to a lack of reaction for others for whom the lack of spontaneity in each sequence was a real sticking point.

Cleese was supported, as in Fawlty Towers, by a sterling cast of British character acting talent, mostly in bit parts, from Stephen Moore as the vague music teacher to Joan Hickson as one of a trio of senile old ladies Steadman looks after, to Tony Haygarth as a tractor-owning farmer, Michael Aldredge as a sympathetic monk (his facial expressions are a highlight) and Geoffrey Palmer at the conference. Also spotted was Sheila Keith as Penelope Wilton's mother, noticing Stimpson vandalising a telephone box, and leading Wilton to regret helping out her old flame. As you can see from that sample, this was heaven for “that guy” and "that gal" spotters, but unlike Fawlty, we don't feel this chap deserves his downfall, there are worse things than punctuality, and it can all feel somewhat cruel. With this assembly of professionals it was never boring, but you may find it contrived. Nevertheless, it was a neat hit for Cleese.

[It's the first time on Blu-ray for Clockwise, released by Studio Canal. Also on DVD, picture and sound are very fine, and the extra features consist of:

Interview with Michael Frayn

Clock watching with Mr. Cleese (a vintage featurette)

Stills gallery.

No trailer, sadly, though anyone around in '86 will have seen it a billion times in the ad breaks.]

|